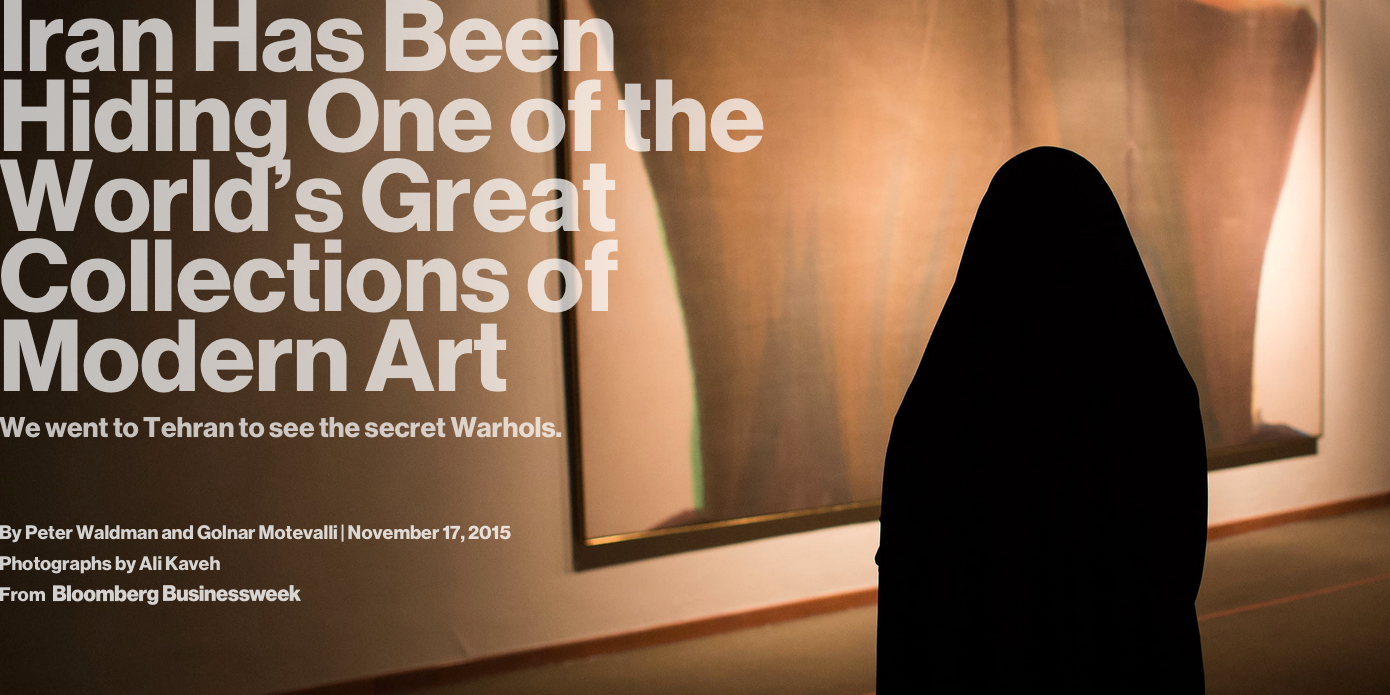

As Iran lurches toward reengaging with the world after the end of years of sanctions, a crown jewel waits in history’s shadow. Built by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s wife, Empress Farah Pahlavi, just before the 1979 revolution, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art amassed the greatest collection of modern Western masterpieces outside Europe and North America—and dropped off the map. Now it’s reemerging. The museum is following up its big abstract expressionism show with a mixed exhibition of Iranian and Western art opening Nov. 20. In October it signed a tentative agreement with the German government to send 60 artworks from Tehran—30 Western and 30 Iranian—to Berlin for a three-month show next fall, which would mark the museum’s first exhibition overseas. A larger show could follow in 2017 at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum in Washington if political and legal circumstances allow, says the Hirshhorn’s director, Melissa Chiu. “This is one of the great unseen collections of postwar European and American art in the world,” she says. “We haven’t seen these works in 40 years.”

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini took power railing against “West Detoxification,” his notion that Western moral and sexual depravity had infected Muslim nations with a disease that could be cured only with strict rule by Islamic clerics. He banned Western films, music, and many books, forced women to wear the hijab, and castigated Iranian elites for being infatuated with foreigners. “With a European hat on your head,” he wrote, “you would parade around the streets enjoying the naked girls, taking pride in this ‘achievement,’ totally heedless of the fact that the historic patrimony of the country was being plundered.” As revolutionary mobs protested in the streets in January 1979 after the shah and his wife fled, the museum spirited its 1,500 works of Western art into a basement vault.

“Art can be a bridge between Iran and the West, but with some exceptions”

When armed militiamen showed up a month later, Mehdi Kowsar, the museum director, made the commander sign an inventory list showing the prices the empress had paid for every piece. Ten days later, Kowsar, a former dean of arts at Tehran University, flew to Italy with his family. He’s never returned. To avoid questions at the airport, he left the list behind at his Tehran apartment. He hasn’t seen it since. “It was a very dangerous situation,” says Kowsar, 79, a retired architecture professor living in Rome. “I was hoping that if they signed something official, no one would steal anything.”

The collection remained remarkably intact, minus an Andy Warhol portrait of Empress Farah, slashed years ago at one of her former palaces by a knife-wielding zealot, and a Willem de Kooning nude, sold to David Geffen in 1994 as part of a three-way trade on the tarmac of the Vienna airport for some 16th century Persian miniatures owned by a Clinton White House operative. More on that later.

The collection’s survival is part of the larger Iranian paradox—the struggle of one of humanity’s oldest and most refined civilizations to overcome an historic spasm of fundamentalism and xenophobia. Yet it’s also the story of a simple man who had no idea what art was before joining the museum in 1977, and who made protecting the Western treasures his life’s work.

If you follow the museum’s snail-shell ramp to the bottom, slip past the velvet rope, go right at the industrial vacuum cleaner, and skirt by the Styrofoam-packed picture frames against the wall, there are two doors. The steel one on the right has a doorbell and a blue sign that says “exhibition services.” It leads to the vault. The door on the left says “photography” and opens into a dimly lit room with concrete walls, a torn couch, and the cozy feel of the super’s office in the basement of a New York City apartment building.

Firouz Shabazi Moghadam sits at a corner desk, below a high window that just clears the ground level. He went to work for the museum two weeks before it opened, first as a driver and then, for 30 years after the revolution, as custodian of the vault. His official title is a keeper. Still lanky at 63, with dark eyes that squint when he smiles, Shabazi came out of retirement two years ago to help catalog the museum’s extensive holdings of Iranian art and photography, in addition to the Western collection, which he knows by heart.

During the 1973 oil crisis, global art prices fell, and Iran got very rich selling oil. In 1976, David Nash, who ran Sotheby’s impressionist and modern painting department in New York, flew to Tehran with a box of slides of paintings for sale by the Los Angeles collector Norton Simon at “ludicrously high prices,” Nash says. He had to wait a week for a promised appointment with the empress’s court chamberlain, who proceeded to spend the meeting lecturing Nash on an obscure copyright dispute Iran was having with Sotheby’s at the time. He left the slides behind and went home, certain the trip had been “a complete fiasco.”

A few days later, the chamberlain’s office asked Nash for advice. What should it bid on at Sotheby’s coming auction, the estate sale of Holocaust survivor Josef Rosensaft? He suggested a few works; Iran bought the entire lot. The haul included Paul Gauguin’s 1889 Still Life With Japanese Woodcut, which cost $1.4 million, a record at the time for the artist. Nash says it’s worth $45 million today. Majid Mollanoroozi, the museum’s director, says Japanese collectors have offered “a blank check” for the painting.

“They’d say, ‘What is this? I could do better than that,’ ” Shabazi says. “I’d tell them it’s a Picasso, and they’d say, ‘So what if it’s a Picasso!’ ” As chaos engulfed Tehran’s streets, Shabazi spent most of the next two years locked in the vault with the artwork and the keys. “I didn’t want anything to happen,” he says.

The main galleries of the museum reopened as an exhibit hall for revolutionary propaganda, cheering martyrdom and resistance during Iran’s eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s. Occasionally people showed up at the vault with official letters demanding to borrow paintings for a cultural center or one of the shah’s opulent palaces, which had been converted into public amusements. Shabazi refused to unlock the doors, suspecting such loans would never be returned. “Only God knows where I got this courage from—I who am normally so afraid,” he says, with tears in his eyes. “With this vault, with this museum, I am like a lion.”

It wasn’t until 1999, a decade after Khomeini’s death and 20 years after the shah fled, that the museum mounted its first post revolution Western show—a pop art exhibit featuring works by Hockney, Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg, and Warhol. An uneasy détente has settled in, mirroring the seesawing ascendancy of reformists and hard-liners in Iranian politics. Since 2013, technocrats in the economic and cultural ministries, appointed by President Hassan Rouhani, have tended to push the revolution’s boundaries against conservatives in the security and judicial establishments, which are controlled by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

At the museum, that means the directors, who report to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, hang a few dozen Western pieces each year for several weeks. They’re careful—usually—not to rile government conservatives with racy images, or bait them with the idea that the museum’s most significant portfolio is its world-class collection of post-World War II works by Americans, many of them gay or Jewish. The role of Empress Farah, now 77 and living in Washington and Paris, remains publicly unmentionable.

The vault holds a small treasure trove of artwork that Iranians will never see, at least while the current regime is in charge. It includes nudes by Pablo Picasso and Edvard Munch; a large canvas by Andre Derain, called Golden Age, depicting 11 unclad women frolicking in nature; and Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Gabrielle With Open Blouse, a beguiling portrait of a bare-chested young woman with her shirt unbuttoned to her navel.

“I said ‘Look, they’re male figures, they’re not female, and they’re semi-abstract. It’s not obscene. They could be brothers,’ ” chuckles Sami Azar, who now lectures on art at a Tehran gallery. “They said, ‘C’mon, we know they are homosexuals, they’re sleeping in bed. This creates a scandal for us, just when conservatives are coming to power and looking for excuses to bombard us.’ ”

The ministry’s written order didn’t come until after the guests arrived. They got to see the complete triptych on their way in, and a nail where the panel with the sleeping men had hung on their way out.

“Art can be a bridge between Iran and the West, but with some exceptions,” explains Hossein Sheikholeslam, one of the student radicals who occupied the U.S. Embassy in 1979 and went on to serve in several prominent positions in the revolutionary government. “Nudity and homosexuality are not acceptable in Iranian culture,” he says.

You can’t hear the doorbell ring from outside the double gray doors of the vault, but the slam of a deadbolt signals someone is coming. Inside is another doorbell and another steel door, this one about six inches thick with a black combination lock above the handle. It creaks open, revealing a long concrete room with 32 floor-to-ceiling sliders—wire-mesh slats framed in steel—pushed against the wall on both sides. Only two paintings are visible: a dour portrait of Ayatollah Khomeini on floor blocks to the right and Picasso’s 45-square-foot masterpiece from 1927, The Painter and His Model, on the far wall, acclaimed as “one of the supreme achievements of his career” by art historian Jeremy Melius of Tufts University.

Starting next to the Picasso, Shabazi and his handpicked successor pull the sliders screeching on their tracks into the center of the room for viewing, oldest paintings first. It looks like a poster store, with images hanging by the dozen on each metal fence. The collection starts in the late 19th century with works by Monet, Gauguin, Pissarro, Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, and Rodin. Toward the mid-20th century, one slider alone holds 10 Picassos (of the museum’s roughly 30), two Marc Chagalls, a Georges Braque, and a Diego Rivera.

The bulk of the collection, from after World War II, is found in the vault just past the air-conditioning duct. There are about a dozen Jasper Johnses and Robert Rauschenbergs each and at least 15 Warhols. Among them is a Warhol Mick Jagger, a Marilyn Monroe, and a series of 10 Maos. Most valuable is his 1963 acrylic of a man jumping off a building, called Suicide (Purple Jumping Man). Another of Warhol’s rare Death and Disaster paintings sold for $105 million in 2013.

Shabazi’s favorites: the Rothkos, he says, pulling closed the heavy vault door behind him. “I’ve had a lot of problems in my life, and they always calm me down.”

The museum gets frequent offers to buy its paintings, most recently from a Monaco foundation that wants to buy Bacon’s triptych for €103 million ($110.7 million). But nothing’s for sale, not even the works deemed unpresentable, says Mollanoroozi, the director. “If we sell them, what would we buy instead worth that much?” he asks. He’s hoping revenue from the overseas shows will fund the museum’s first acquisitions in 40 years, as well as needed improvements such as new lighting and carpets and waterproofing to protect the vault in a flood.

About 12 years ago, Sami Azar hired Christie’s to value the nudes, hoping to use the proceeds from a sale to update the collection. Then-President Mohammad Khatami approved the idea but said parliament should make the final decision. Sami Azar decided not to risk it. Selling the art is easy, he says. Getting the money back from the government to buy more could be treacherous.

The deal took three years to negotiate. At first, the intermediaries demanded five paintings for the Shahnama, including the prized Pollock, a Miró, a Picasso, and Renoir’s revealing Gabrielle With Open Blouse. Hojjat took the matter up to Iran’s Supreme Cultural Revolutionary Council for a decision, providing photographs of each of the works. In the end, the Iranians would give up only the de Kooning, which depicted a grotesque, misshapen woman without any clothes on.

Shabazi remembers loading the painting onto the jet at dawn in Tehran. Hojjat, worried the U.S. government might try to seize the work as compensation for other disputed assets, arranged to have it whisked away from the Vienna tarmac to an art dealer in Switzerland. At the same time, the Shahnama was loaded onto Hojjat’s plane and flown to Tehran. The de Kooning was sold to Geffen in California for an estimated $20 million. The Houghton family received $10.5 million of those proceeds for the Shahnama, much of the rest going to middlemen. Geffen resold the de Kooning in 2006 to hedge fund magnate Steven Cohen for $137.5 million.

Hojjat recalls the most surprising comment he got during the long talks over what Iran would or wouldn’t exchange for the Shahnama. One of the religious authorities on the supreme revolutionary panel was quite adamant about Gabrielle With Open Blouse, a portrait of the woman who worked for the Renoir family as a nanny. “This Renoir painting is very exquisite,” the man said. “Do not give it away.”