A report in The Australian Women’s Weekly at the time began: “Everyone wanted to see Empress Farah wherever she went on her eight-day visit … One of the most elegant and beautiful women in the world, with a quiet charm and warm brown eyes …” Quite apart from her day-to-day polish, her YSL wedding dress and coronation crown made to design by Van Cleef & Arpels were hard to forget.

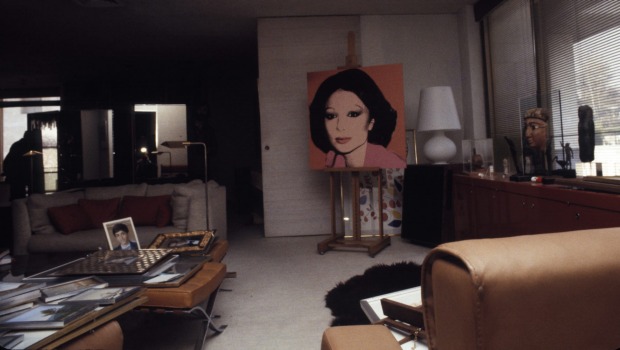

Just one year earlier, the empress had been trying to buy Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles at the same time as the Australian National Gallery in Canberra. The negotiations were delicate and secret. Canberra won and Australians fumed, both at the painting’s abstraction and the $1.3 million cost. Pahlavi went on to acquire Pollock’s 1950 masterwork, Mural on Indian Red Ground. Along with works by Picasso, Gauguin, Giacometti, Warhol, Bacon, Rothko and other luminaries, it formed the backbone of a collection of modernist and contemporary works deemed to be the largest outside Europe and North America.

During the late 1970s, when the Shah was facing rising domestic opposition to his authoritarian rule, his wife was championing cultural awareness. On October 13, 1977, her grand project, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, opened with great fanfare. The museum became an international symbol of her work, a cultural complement to the Shah’s moves towards modernization, his “White Revolution”. She promoted women’s rights, established literacy programs and mobile libraries, and launched a film festival. She gave blood and encouraged Iranians to do the same. She established the first self-sustaining leper colony in Iran and visited its residents.

Within two brief years, all that was finished. The 1979 revolution sent the Shah and the Shahbanu into exile. World leaders, such as Jimmy Carter in the US, who had extolled the greatness of Iran’s leader, refused them refuge. The revolutionary collaboration between Marxist students, imams, and others opposed to the Shah’s wealth and extravagance, his adoption of Western ways, and the operation of his terrifying and ubiquitous secret service, the SAVAK, soon devolved into religious rule under Ayatollah Khomeini, who railed against “West detoxification”. The Ayatollah banned Western books, music, and films, and forced women – who had been granted the vote under the Shah in 1963 – back into a hijab. The empress’ art collection was transferred to the basement of the newly built museum.

It has not been seen again except in rare circumstances: the last time was in 2005 when some works not deemed offensive to Iran’s religious sensibilities – including the Pollock – were displayed. A loan of 60 works to Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie last year was inexplicably blocked by the Iranian authorities at the eleventh hour. Today the collection is estimated to be worth $US3 billion ($3.9 billion).

Book and film tell the story

The story of Farah Pahlavi’s lifelong love affair with the arts, the museum she founded, and its hidden art collection is the subject of a forthcoming book by Australian author Miranda Darling and London-based art adviser Viola Raikhel-Bolot. The pair have also established a company, to make a documentary celebrating the life of Pahlavi, the first in a planned series about women influential in art history. They are already filming in Britain and are negotiating with Iran.

Through her art world contacts, Raikhel-Bolot secured Pahlavi’s collaboration with their project. “She speaks in this beautiful gravelly voice with a lovely accent,” Darling says. “Things like that are very atmospheric so she’s wonderful to have on film. She’s very elegant and engaged, and tells a great story.” Pahlavi helped the authors with research for their 200-page book, which features more than 100 illustrations and will be published by Assouline in September. Unusually, the text and even the title are being held tightly under wraps. The documentary is provisionally called Tehran Hidden Vault of Modern Masterpieces.

Author interest in Iran and art

The two authors have their own links to the region. Raikhel-Bolot – Azerbaijan-born, LA-raised, and now London-based – is a prominent corporate art adviser. She and her company, 1858 Ltd Art Advisory, constantly pop up on lists of ‘who’s in the know, from high-end investment advisers to fashion mavens. Darling – journalist, novelist, and a scion of the prominent Australian business family – also move

around the world constantly as a child, hostage to her father’s work as a management consultant. Educated at Oxford University, Darling now moves between Britain, Zurich, and her Bondi home base.

documents when the subject of the ill-fated Iranian prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, comes up, as it surely does in connection with that country’s turbulent history (the CIA has just released documents showing its involvement in the 1953 coup that deposed him), Darling says airily: “My grandfather [a geologist] was there, finding oil for the Shah. My mother grew up there, she remembers it.”

Raikhel-Bolot and Darling are steering clear of politics in their project, but not with the aim of airbrushing history. “We know it. People know it. It’s an unavoidable backdrop,” says Raikhel-Bolot, of the repression under the Shah which fueled the 1979 revolution. “And you don’t have to say, ‘Look at what it’s like now.’ When you see a picture of a veiled woman in front of a Rothko, it’s striking.” Darling adds: “We chose to not engage with that. A lot of people might not have talked to us, whereas they are happy to talk about art and culture. So, in a way, it’s just as well.”

Pahlavi’s art collection is still in the basement of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, which shows only “appropriate” works. It’s ironic that one of the paintings brought up briefly for public display 12 years ago was Jackson Pollock. The abstract expressionism of Blue Poles may have provoked debate about the nature of art in 1970s Australia but in contemporary Tehran, it is figurative artwork that is problematic because Muslim religious art avoids the depiction of living beings.

As Darling points out: “Had she bought Renoir, that would have been more controversial than the Pollock.”

Poles may have provoked debate about the nature of art in 1970s Australia but in contemporary Tehran, it is figurative artwork that is problematic because Muslim religious art avoids the depiction of living beings. As Darling points out: “Had she bought Renoir, that would have been more controversial than the Pollock.”

Article by: AFR MAGAZINE

by Kaveh Kazemi