He was laid to rest in the Al- Rifa’i Mosque, also known as the King’s Mosque, in Cairo. Their two youngest children, Princess Leila, and Prince Ali-Reza, who never reconciled with life in banishment, took their own lives. As I consider these misfortunes, from the window, Her Majesty turns, smiles, and says, “I am not bitter. Such thoughts only invite the enemies to win.”

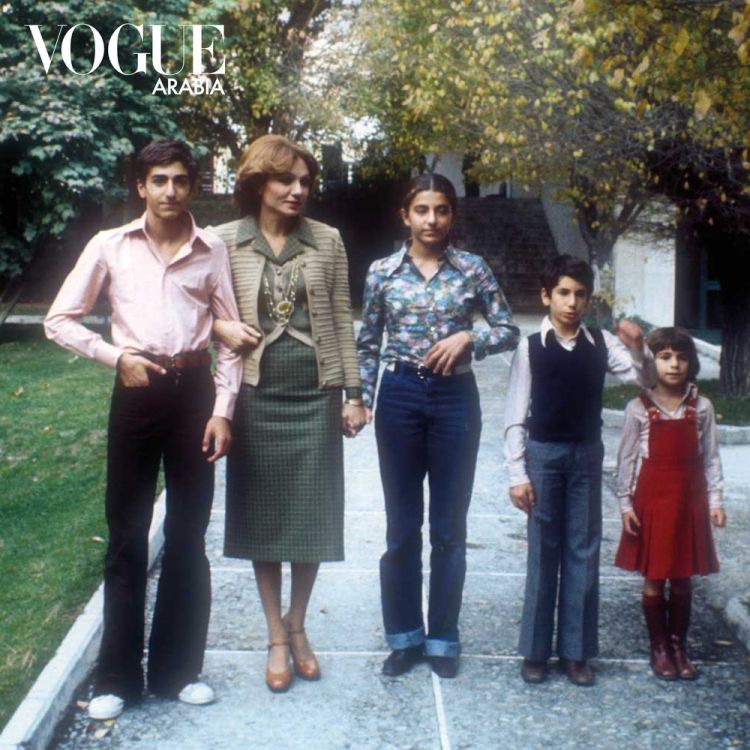

It is only a few days into the new year, and though not particularly cold, the city is moody. What little light enters the floor-to-ceiling, wood-paneled salon dims considerably during my three-hour audience with Her Majesty, until we are almost cloaked in darkness. Sitting to my left on a white cushion couch is the Queen’s 26-year-old granddaughter, Her Highness Princess Noor Pahlavi. The firstborn of Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi – the man who would have been shah – is an MBA student at Columbia University and an advisor to the non-profit impact investment fund Acumen. In black leggings and a red sweatshirt, her frame is as slight as a couture model.

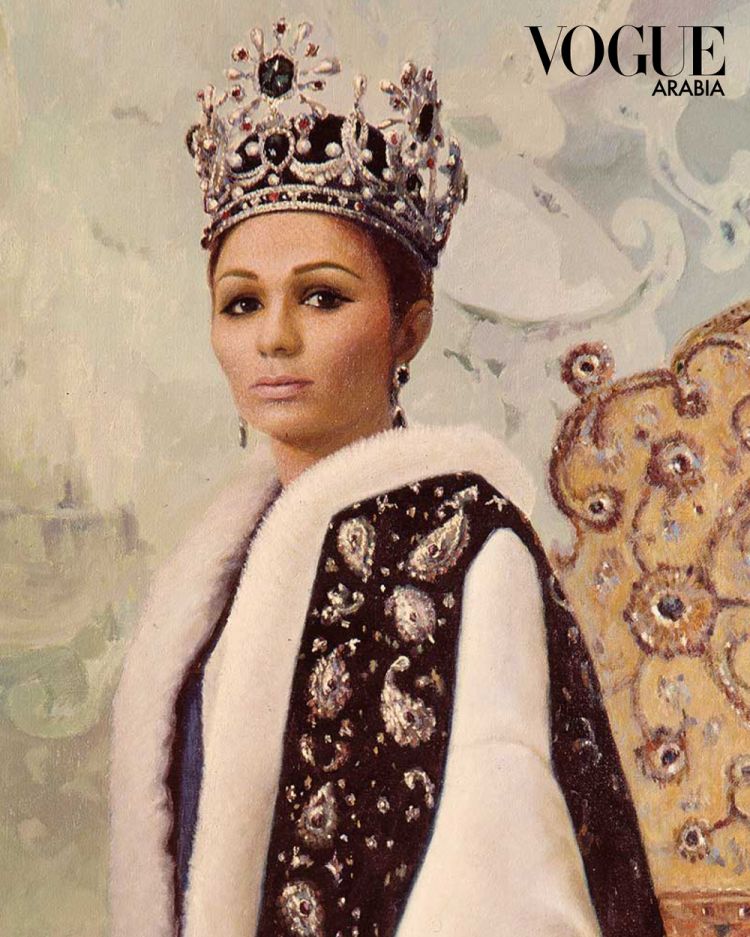

“My memory is not what it was,” starts Her Majesty, when I ask her to recall her emotions at the birth of her first granddaughter in Washington. “I was just happy to have a healthy grandchild.” How different the scene, when Queen Pahlavi – the third wife of the Shah, following his divorce from Princess Fawzia Fuad of Egypt and Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari – gave her husband and country a long-desired male heir. “My wedding dress was designed by Yves Saint Laurent, who was working for Dior at the time. His seamstresses sewed blue thread in the dress to help me have a boy,” she recalls, smiling at the memory.

With a slight shake, as though she is physically stepping out of the past, the Queen next pronounces that her granddaughter has a talent for painting.

A few weeks after the interview, I am on the phone with one of the one million registered displaced Iranians. She agrees to speak with me on condition of anonymity, to protect her family in Iran. “Queen Farah is very popular, well-loved, and respected. We call her ‘Mother of Iran,’” she starts. “As queen, she was always encouraging women – she did things that other wives of shahs had no history of doing. She played a big role in women’s lives at a time when we were starting to become equal to men, including joining the army – all the things not possible before,” she shares. “I had finished law school and, after the revolution, was building a practice with my brother.

Today, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2018 Global Gender Gap Report, Iran ranks 142 out of 149 countries. Iranian women are systematically barred from social, educational, and legal rights and protections. The princess underlines the disparity between people living in the city versus those in provincial villages. “There are drastic differences, even in healthcare, available to women.

From a fifth-floor window overlooking Paris’s murky Seine River, an 80-year-old lady stands straight and tall; the white of her pantsuit illuminating the dull, surrounding wintery gray. Her Imperial Majesty Empress Farah Pahlavi, the last queen of Iran following 2 500 years of imperial rule, is as still as a sculpture. I observe her quietly from the doorway as she appears to undulate between myth and reality.

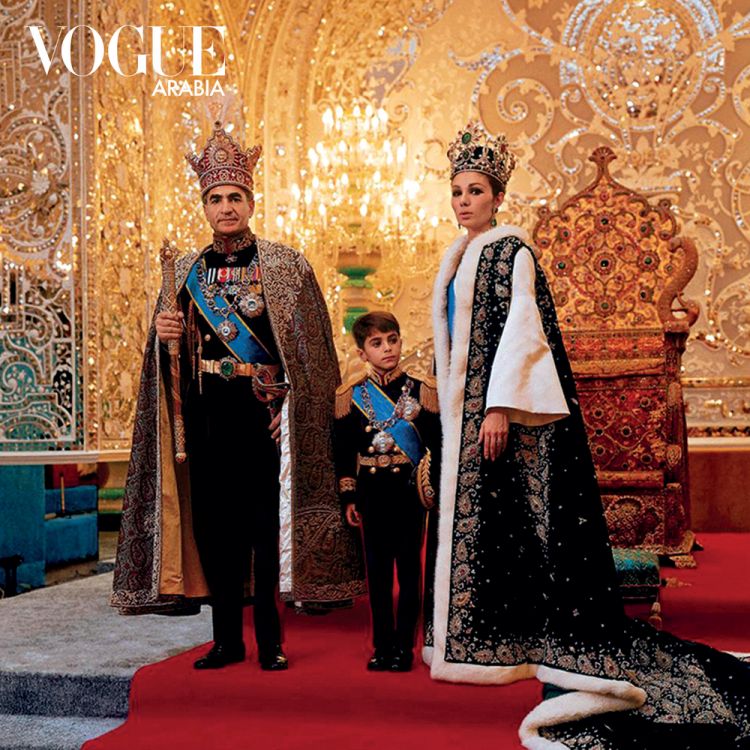

Forty years have passed since the Queen and her late husband, His Imperial Majesty Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was forced into exile during the Iranian Revolution. On January 16, 1979, the Shah piloted his Boeing 707 with his wife and their closest confidants on board out of Iran for the last time. The path thereafter would be long and at times tragic. The King would die of lymphoma cancer 18 months after being forced out of the homeland he ruled for 38 years.

We speak uninterrupted for hours, but it is the following day, when the Queen’s residence is alive with the photo shoot crew, that I witness a feisty exchange common to the family. “There is nothing wrong with this dress!” exclaims Princess Noor to her grandmother. She is wearing a skin-toned Dior gown; its delicate bustier resembles a sleeveless unitard. While she appears like a ballerina, the Queen firmly objects to the attire. The shoot has not yet begun and she can shut down production at any instant. Princess Noor’s outburst is not the nature of a glamour-seeking woman, however. Rather, that of one stifled by the weight of a regime that now demands women to be modest.

Her great-grandfather, Reza Shah Pahlavi, founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, decreed the removal of the veil in 1935. The veil returned as a symbol of resistance against the imperial dynasty during the revolution of 1979, led by Ayatollah Khomeini.

You would have all these art supplies at the house in Greenwich.” The Queen is swiftly drawn back into her memories. “After I lost my son Ali-Reza in 2011 – he was so intelligent and hardworking; he knew the history of Iran unbelievably well – a friend of mine, said, ‘Why don’t you come to my house and draw?

The Queen’s two-story Paris residence, with winding hallways and hidden rooms, is filled with family photographs of smiling faces celebrating Iranian traditions, such as burning Esfand as incense and fire-jumping Chaharshanbe Suri, and joyous milestones, like birthdays and graduation ceremonies. “I keep all the letters, pictures, newspapers, and so many books in this house and in the US – I’m what Americans would call a ‘hoarder,’” smiles the Queen. “I wonder what will happen to all this,” she ponders, looking around. On the second floor of the apartment hangs a painting of the late King and the Queen on a motorcycle. “It’s my favorite image of her,” says Princess Noor. “It makes me think, my grandmother was a badass.” “A what?” her grandmother laughs. “A badass, Mama Yaya,” repeats the Princess articulating each syllable. Certainly, no one has ever dared refer to her as such in her presence. “I was on a motorcycle on Kish Island,” she explains. “I was going too fast and fell.

In 1925, following the 1921 Persian coup d’état, Reza Shah Pahlavi was put on the throne by the constitutional assembly.

“She’s created this open portal into her treatment to raise awareness for breast cancer and women’s health,” says the princess, proudly. “But what she discovered is that in Iran, a lot of care surrounds reproductive health only. Apart from delivering a child, a woman’s feminine care is ignored.”

“Some of the older generations ask, ‘Why does she talk about that?’” notes the Queen. “But it’s very positive that she opens up to people.”

Princess Noor continues, “My mom wants to see certain cultural stigmas eliminated. She’s received a lot of heat throughout her marriage – sometimes for just traveling without her husband. I don’t know if it’s because she is a woman, or if it is just an idea of what the imperial family should be. But for her, speaking out about her illness is important.” She adds that was her mother not living and being treated in the US, she might have died.

As if for comfort, Princess Noor gives her grandmother’s Cavalier King Charles spaniel’s belly a rub. Mowgli, a gift to the queen from her granddaughter, has spent the past few hours alternating between the women’s affections. Looking tenderly at her Mama Yaya, Princess Noor comments, “She is kind to all living things and has empathy for anything innocent. Seeing her experience so much and maintaining her composure, we feel stability and strength in turn.”

Of her aspirations for the Pahlavi legacy, which she will one day carry on her slight shoulders, she comments: “Our legacy lives on today – because of the contributions my family has made and the beliefs we espouse.” She stresses that her father advocates liberalism and democracy. “Iran means everything to us, but whether we occupy any official role in the future is not up to me but to the people. The future is in their hands, as it should be.”

Photography: Stéphanie Volpato

Style: Sarah Cazeneuve

Hair: Olivier Lebrun

Makeup: Camille Siguret

With Special Thanks To Nazy Nazhand.