Interviews

23

Mar

2019

Life Beyond the Peacock Throne

He was laid to rest in the Al- Rifa’i Mosque, also known as the King’s Mosque, in Cairo. Their two youngest children, Princess Leila, a...

04

Jan

2018

Iranian people can bring change

CAIRO – 2 January 2018: “Iranian people have the unwavering ability to bring about the desired change,” Iran's former Empress Farah Deb...

01

Aug

2017

Gratitude towards the Egyptians

CAIRO - 30 July 2017: On January 16, 1979, the Shah of Iran Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left Tehran after being overthrown by the Iranian Isl...

28

Feb

2017

The collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art

The collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was to be shown in Berlin in December, but Iranian officials declined permissio...

26

Feb

2017

Former Empress of Iran: “We wanted to create progress”

Within the basement of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, sealed away from public view the majority of the time, there lies a colle...

10

Jan

2014

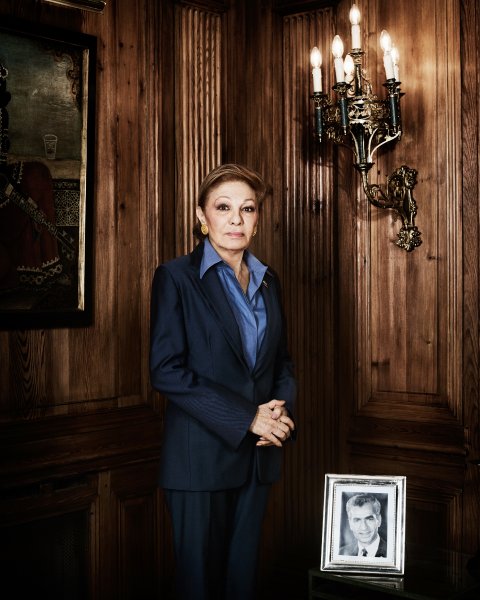

When there is pressure, artists become creative

Her Imperial Majesty Empress Farah Pahlavi of Iran—as she was officially known until 1979, when her husband, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi...

13

Dec

2013

Exclusive interview with Point De Vue

Her Majesty Queen Farah Pahlavi exclusive interview with Point De Vue on her 75th Birthday

75 Years of a life like no other and a cont...

17

Nov

2011

Shahbanou with her 4th granddaughter

Princess Iryana, The daughter of the late Prince Ali Reza and Miss Raha Didevar, was born on July 26th. A few days ago, Shahbanou Farah...

01

Jan

2010

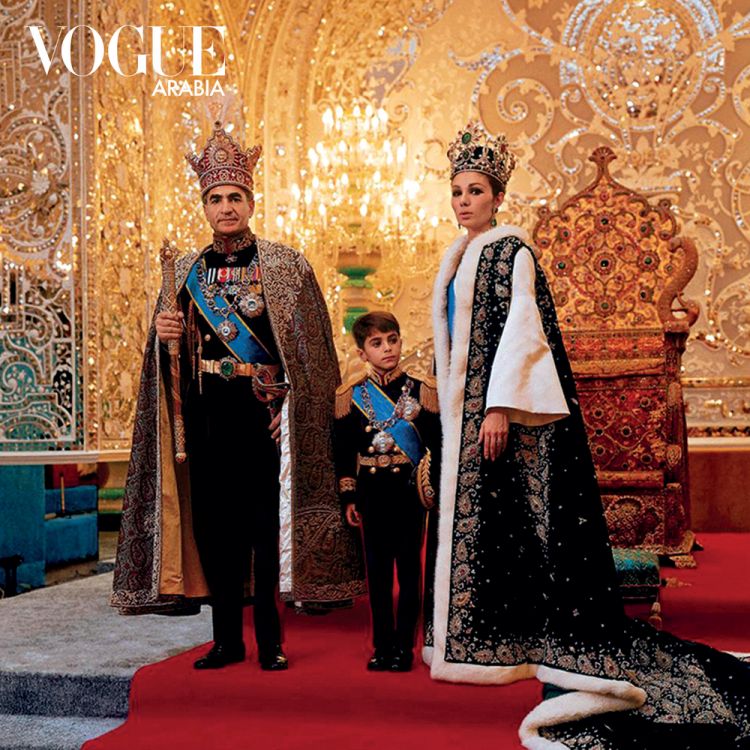

Her Majesty Farah Pahlavi The Queen of Culture

In an exclusive interview with Canvas, Her Majesty Farah Pahlavi reveals unchanged and enduring passions: art, culture, her compatriots...

15

Sep

2009

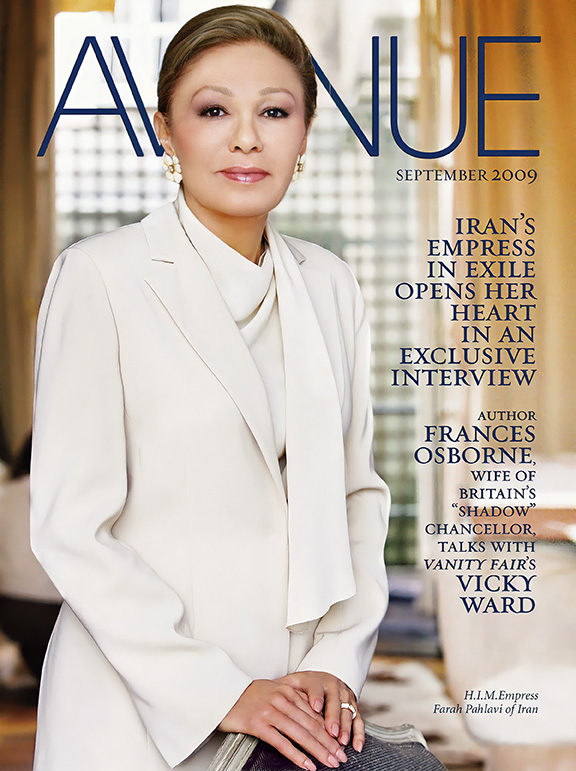

Iran’s Empress Opens Her Heart

Half a century ago, then-Miss Farah Diba married the shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who crowned her Shahbanou, or Empress, eight ...