The collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was to be shown in Berlin in December, but Iranian officials declined permission to send the artworks out of the country. SPIEGEL spoke with former Empress Farah Pahlavi, who assembled the collection in the 1970s. She’s been living in exile for 38 years.

The photos of the opening ceremonies for the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art from 1977 depict a country that no longer exists. They show men dancing bawdily in tight pants and dark glasses while female performance artists are dressed only in red wool yarn. The hedonism of the 1970s is on full display in the images, demonstrating that Tehran, too, was experiencing the rise of a younger generation.

These images, which are now on display in the Box Freiraum exhibition space in the Berlin neighborhood of Friedrichshain, were taken by the Iranian photographer Jila Dejam. Originally, the photos were to accompany a planned December exhibition in the Gemäldegalerie art museum in Berlin of works from the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. The exhibition had been conceived as a symbol of cultural rapprochement between the West and Iran following the so-called nuclear deal.

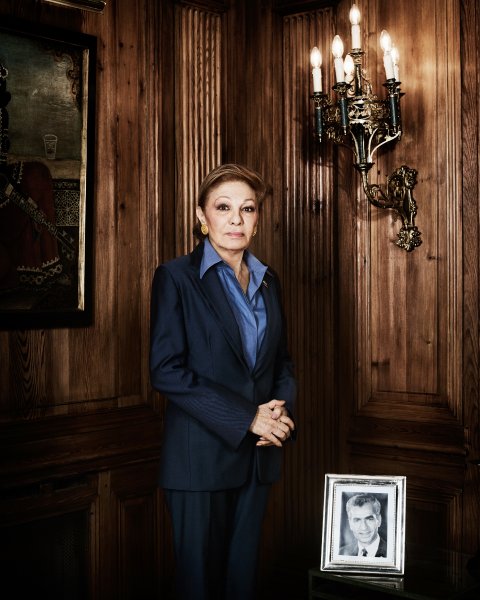

The empress of Iran at the time, Farah Pahlavi, had initiated the collection in the 1970s, partly in pursuit of the dream of establishing Iran as a cosmopolitan, modern country, which at the same time was cruelly unjust. The 1979 revolution ended the dream, but amazingly, the artworks themselves survived. They lie essentially inaccessible in the museum’s basement.

During a visit to Tehran in 2015, then-German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier received permission for an exhibition in Berlin of 60 Iranian and international works of art from this collection, including a painting by Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollack’s “Mural on Indian Red Ground.” Hermann Parzinger, president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, said of the potential exhibition that he hoped it wouldn’t just promote dialogue with Iran, but also strengthen “liberal forces, civil society.” Ultimately, however, official permission to send the artworks to Berlin was withheld.

Farah Pahlavi, who is now 78 years old, has been living in exile since 1979. She receives guests in her Paris apartment, surrounded by modern art and pictures of her family.

SPIEGEL: Madame Farah Pahlavi, would you have traveled to Berlin to see the exhibition of the art collection that you assembled in Iran?

Pahlavi: Oh yes! I would have definitively traveled to Berlin and visited, although only after the official opening. They could not have stopped me. It is a free country!

SPIEGEL: When you say “they,” you mean the Ayatollah regime in Tehran?

Pahlavi: Yes. The exhibition was interesting for me for two reasons. First, it would have shown the positive things that were done before the revolution, during our time. Second, all of a sudden people, the media, were speaking about me again, about what we did and not so much about what the current regime is doing today.

SPIEGEL: The Iranian government declined to grant permission for the art collection to leave Iran. Are the ayatollahs still afraid of you 38 years after Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi left Iran?

Pahlavi: Many people are still talking about my husband. It gives me energy and courage that Iranians on the street, both here in Paris and in the U.S., kiss and hug me out of the blue, especially young people; people who were born after we had to leave. Through the internet and television, they know what Iran was like at that time. They know what it could have been today, and they blame their parents for what happened.

SPIEGEL: With the cancellation of the exhibition, did Iran and the West, and did Germany, miss an opportunity for real rapprochement?

Pahlavi: If you want to create a dialogue that might help open Iran, it takes more than showcasing a Picasso. You would need to do something inside the country, to work for more freedom, for more human rights. But Germany has already started doing business again with Iran. To me, it seems that this is more important than anything else.

SPIEGEL: Why did you begin buying modern art when you assembled your collection?

Pahlavi: In the early 1960s, I went to many art galleries, met artists, and bought their work. The wealthy people of Iran were buying old Iranian art, not the work of modern artists. A female painter told me: “I wish we had a permanent place to keep our works of art,” and the idea was born to build a museum for Iranian artists. And why not have foreign artworks as well, when the rest of the world has Iranian art in their museums?

SPIEGEL: The collection’s curator, Donna Stein, came from the U.S. The dance performances at the opening ceremony were quite avant-garde; some were downright lascivious and provocative, at least for a rather traditional and conservative country like Iran at the time. Most of the population lived in poverty. Did you live in a bubble?

Pahlavi: I don’t think so. Iran was not a conservative country. I don’t know why some people think that only the West can have contemporary and modern art museums. I was traveling a lot in Iran and talking to people. My husband was working to bring the country forward. He called it the White Revolution.

SPIEGEL: A program to modernize the country, intended to reduce the influence of traditionalists.

Pahlavi: We were looking to become a modern country. My husband initiated land reform to bring the feudal system to an end; equal rights for women; worker rights; and the nationalization of forests and water supplies. Education, hospitals, libraries, economy and industry: We wanted to create progress. The religious people, of course, like Ayatollah Khomeini, were against all that.

SPIEGEL: A U.S. newspaper wrote at the time that the opening of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was akin to provoking a clash between one of the world’s oldest civilizations and the modern Western world of the 1970s.

Pahlavi: In a way, this is looking down on Iranians. Iranians have so much culture and history. Persepolis was built by workers who were paid, not by slaves. Cyrus the Great’s cylinder, from the sixth century B.C., was a precursor of the United Nations human rights charter. People say, “you went too quickly.” But what progressive government doesn’t want to go quickly? I remember a conversation with Henry Kissinger in Egypt many years ago when I said that maybe we should have opened up society five or six years earlier and the revolution would not have happened. He replied that (had we done so) it would then have happened (five or six years) earlier.

SPIEGEL: The collection contains Francis Bacon’s “Two Figures Lying on a Bed with Attendants,” showing two naked men lying together. Was this appropriate for 1970s Iran?

Pahlavi: There was no reaction to such paintings when the museum opened. Everybody was very happy and proud. Not everybody in society accepted gays then. They were there, but not as open as they are in today’s Europe. But these people now …

SPIEGEL: … you are talking about the revolutionary clerics?

Pahlavi: Correct. They say they don’t like this picture. But please, remember what they did when they took over: They raped virgin girls who were opposed to them before hanging them – to make sure they wouldn’t enter paradise.

SPIEGEL: The revolution began only a few months after the museum’s opening. Wasn’t the revolution also a reaction against the deep divide in society, the inequality of wealth distribution, and the lifestyle of the elites?

Pahlavi: I never heard any criticism about the museum. Everybody was happy about it then and everybody is happy about it today. It is a crucial cultural heritage and I don’t even know how much more valuable it is now than it was when I created it.

SPIEGEL: How was it that you failed to recognize the dangerous societal undercurrents that ultimately swept you away?

Pahlavi: We didn’t manage the situation well, otherwise it would not have happened. Our enemies were well organized and we were not. Many of them were trained in camps in Palestine, Cuba, and other places.

SPIEGEL: The Shah had one of the largest and best-equipped militaries in the region.

Pahlavi: The communists from the Soviet Union, from China, and the leftists, were against us and joined hands with Khomeini. My husband called it an unholy coalition of red and black, where red was the communists and black was the religious zealots. Maybe we didn’t know what was happening in the mosques and underestimated what these people were doing. We couldn’t believe that, after all the Shah had done for the country, he would be replaced by somebody like Khomeini. The publicity against Iran from America and Europe also helped them. Khomeini’s speeches were broadcast on BBC before the tapes reached Iran.

SPIEGEL: Many hated the Shah, but at the same time, many liked you, the empress. One prominent Ayatollah offered you a safe return to Iran if you killed your husband first.

Pahlavi: I don’t consider these people Iranians. They killed so many people.

SPIEGEL: Before the revolution, the notorious intelligence service SAVAK employed systematic torture against the opposition to silence them or to get them to talk. They used electric shocks, burns, the extraction of nails and teeth, and rape.

Pahlavi: There were many lies and exaggerations. A number of leftists who initially supported the revolution later went on the record in the Iranian media to confess that they were propagating these lies, which worked. I would like to refer you to the findings of Dr. Emadeddin Baghi, a former seminary student commissioned by the Islamic Republic to ascertain the number of political prisoners in the Pahlavi era. Mr. Baghi was quite surprised to discover that the actual number of political prisoners was 3,200 rather than the 100,000 reported.

SPIEGEL: An internationally recognized study of the number of political prisoners and murders has never been conducted. But even if it was much lower, they were still human rights violations. Why didn’t you intervene?

Pahlavi: I couldn’t do anything about it.

SPIEGEL: You were the empress. You and the Shah could do anything.

Pahlavi: No, it wasn’t that simple. There was a government and there were other influential people.

SPIEGEL: Was it necessary to torture, to kill?

Pahlavi: No. And if it is true, I regret that they did this. I wish they hadn’t done it. Thirty-eight years have passed and all these negative and highly exaggerated stories have been repeated over and over. I wish you would write about what is going on in the Islamic Republic today.

SPIEGEL: Madame, we cover it extensively. Did you know about torture?

Pahlavi: I had heard about it, but I wasn’t really sure whether it was true. You’re comparing our country with Western democracies, but we couldn’t create democracy overnight. It takes time for people to get educated and to become politically engaged. I was involved in so many activities to bring the country forward: helping with leper hospitals, helping the mentally underprivileged, those who could not see, those who could not hear. We made films, published books, and opened children’s libraries all over so people could learn how to read. We brought books to the most remote villages with jeeps, with donkeys. You have to judge everybody on balance, all the positives and all the negatives. In the life of my husband, I think the positives outweigh the negatives.

SPIEGEL: Should your husband have been more decisive about cracking down on the uprising?

Pahlavi: No. Many people wonder why the Shah didn’t act more strongly in the beginning by just killing people or throwing more of them into jail. But my husband would say: “I don’t want to keep my throne over the bloodshed of my people.” And the Western world helped (the uprising).

SPIEGEL: After you left Iran, no country wanted to accept you and your family. How does one survive such a precipitous fall?

Pahlavi: Sports helped me. I forced myself to play tennis. There were still people who supported us. I always knew who my husband was and I knew who I was. I wanted to keep the spirits of my husband and my children high, also for my own self-esteem. I knew that if I was suffering, my enemy wouldn’t suffer.

SPIEGEL: Did you become depressed?

Pahlavi: I did. I went to a psychologist. I had to take medication for a time, but then I stopped because it made me feel even worse. Today I tell myself: I have made it so far and it’s been 38 years. And if I drop dead one day, well, I drop dead. So what?

SPIEGEL: Your daughter Leila didn’t survive. She and one of your sons took their own lives.

Pahlavi: It is a wound in my heart that will never go away. They were both so intelligent and so hard working with all their problems. People were shouting in the street “Down with the Shah” and things like that, and we were moving from one place to another. At a young age, they heard so many negative things, on television, and in the newspapers. God knows. I often think, what could I have done? But it’s no use, they are not here anymore.

SPIEGEL: What will the future bring for Iran?

Pahlavi: I always want to remain positive. In our long history, Iran has been invaded by so many other countries and despite it all, the Iranian identity has survived. People are very courageous, especially women, who are braver than men.

SPIEGEL: Madame Farah Pahlavi, thank you for this interview.

Article by SPIEGEL